The history of corporate rights and how they became more important than people

by Sara Cameron

In one form or another the concept of ‘business’, that is the trade of goods and services, has existed since ancient times. However, the modern take on business, to include a large scale enterprise whereby groups of people come together to generate large scale profit, is a more recent development. Just as cells mutate, adapt and undergo a process of natural selection, our understanding of business has evolved into what we see today, with the formation of vast industries composed of competing companies and markets all hungry for domination and increasing margins for their success.

The UK is now one of the world’s most globalised economies. This status has been borne out of the routes and resources conquered and colonised during the reign of the British Empire, and the Industrial Revolution rushed through a paradigm shift in our social, economic and cultural conditions as technological advancements meant that agriculture, transportation, mining, manufacturing and labour were radically altered as the country moved into the throes of the 19th Century.

These dramatic changes complemented the burgeoning modern financial system, which developed from merchant banks during the Middle Ages through to a network of banks spreading through Europe during the Italian Renaissance. Money came to be represented as a commodity in and of itself, to be traded and desired as a mark of status. In modern society, banking has become big business, and the financial sector and its controllers operate as a powerful political medium through which national and international decisions are made. As American President Woodrow Wilson once said:

“Some of the biggest men… in the field of commerce and manufacture, are afraid of something. They know that there is a power somewhere, so organised, so subtle, so watchful, so interlocked, so complete, so pervasive, that they had better not speak above their breath when they speak in condemnation of it”

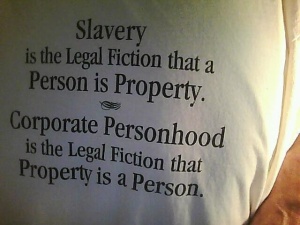

The financial system gave rise to the doctrines and practice of corporatism, in the modern sense of the word, in the 1800s. People could incorporate and create a distinct legal person which could sell shares, limit liability for acts or debt of the company, and reap tax advantages. This structure became the primary form through which economic activity occurs, and a body of civil law exists which provides for the rules in which companies and their members operate. One of the main obligations is that Directors who control the company, have a legal duty to act only in the interests of shareholders who own the company, and of course, shareholders only go into business for one thing, to make lots of money!

Companies can also make use of rights once the preserve of individuals such as those contained in the European Convention of Human Rights, via the Human Rights Act. However, trying to apply real people offences against a company is incredibly limited. Thus, the law surrounding companies is heavily weighted in favour of protecting the people behind the company veil from taking responsibility – as has been evident during the recession which witnessed innocent tax payers foot the bill and then suffer an onslaught of austerity, job cuts and higher living expenses removing any power a UK citizen may have had, whilst those corporations and financial institutions responsible – from large multinationals to wealthy business people – have remained unaffected. Many have even profited from the crisis. George Monbiot in his 2001 book, Captive State: The Corporate Takeover of Britain, hit the nail on the head when he said the following:

“Corporations, the contraptions we intended to serve us, are overthrowing us. They are seizing powers previously invested in government, and using them to distort public life to suit their own ends.”

Perhaps one of the reasons corporate rights have usurped human rights is that of avarice inherent in humanity. But, the pessimism of this ‘one size fits all’, Machiavellian view of human nature is questionable. The link between the political sphere and corporatocracy does seem to go hand in hand when we look at the problem in terms of power. Chomsky asked the right question during a talk in the 1970s at the Poetry Centre, New York: What is the role of the state in an advanced industrial society?

Well, to answer that question, one needs to look deeper into the prevailing political ideology. Since the 1970s, the UK has had a strong conservative and laissez-faire message. From Margaret Thatcher to Tony Blair to David Cameron, unfettered capitalism has appeared in several formations. The State has been rolled back to make way for the individual, whereby citizens are used as instruments to serve free markets under the proclamation that the individual is ‘free’ to pursue their own self interest such as making money and owning private property. However, our system is not truly free – we do not have freedom of thought or expression, for example. Nor, do we possess an egalitarian system since equality of opportunity is, unequal.

The predatory nature of capitalism and private power has taken centre stage. In this type of economy, in order to protect against the physical destruction of the environment and human existence, the State is necessary. The problem, however, is that the capitalist system continues whilst the State keeps being amputated, so there is little in the way of protection from the ills of a rampant system in which people are bound. Rather, questionable policies and self regulatory mechanisms are employed, such as Corporate Social Responsibility in which companies claim to be good for society and the environment, and people understand this to mean something positive. But what happens when a shareholder’s interest conflicts with social responsibility? Well, the law requires that Directors are only responsible to their shareholders’ coffers.

The fact that the law is the preserve of a select few in society, has lead to the prominence of corporate rights over human rights. Company law, with its impact on larger society, is too important to be left to corporate lawyers. In effect, citizens are cut off from understanding and developing the law because they are not able to access the necessary knowledge, nor are they deemed authoritative enough to intervene. Again, this is a failing of our corporate political system for not providing an equal educational system which is accessible for all who should choose to use it. People from deprived backgrounds are offered Academies which have their own agenda depending upon which private company or wealthy individual is sponsoring the school.

Education is only one example, the NHS is being sold off to private companies under dictatorial and expensive governmental private finance initiatives leading to public-private partnerships – the result of which will be a decrease in hospital beds and overall hospitals, thus limiting access to those in need. Supermarkets are becoming more concentrated, so that only a handful now operate in the UK whilst family businesses have been pushed out of the market or bought off. Police forces are also currently undergoing privatisation and employee redundancies, which leaves the question of how a shareholder is to accumulate profit out of the criminal justice system – will new offences appear on the statute book so to arrest more people to make sure that the company is hitting targets?

Equally disturbing is the government’s work scheme, a compulsory programme for people claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance in which they are expected to work remedial, low-level jobs for little payment for corporate entities. Some people forced into these roles may not even be paid for their work at all. Moreover, if one refuses to enter this slave labour agreement, or leaves a programme early, they could see their benefits suspended until they resume the unskilled employment. Recently, the Guardian highlighted the egregiousness of this political scheme when one of its reporters detailed how 30 jobseekers were transported from the South West to London in order to work as unpaid stewards during the multi-million pound diamond jubilee celebrations. They were also told to sleep under London Bridge every night before working on the river pageant. Close Protection UK, which won a stewarding contract for the jubilee events, said that the unpaid work was a trial for the Olympics, which it had also won a contract to staff.

We know that the role of career politicians is to utilise a failed system of governance so to obtain power, status and profit, but how have they and those shadowy figures in the corporate world, achieved such success? With power and opportunity, comes ideology.

Contemporary memories of the British Empire have largely been mediated by popular culture through the media which acts as a vehicle in which to legitimise narratives about the Empire. In the same way, media directed at citizens today exploit commercial themes as the only option, the only thing keeping our world from devolving into a feral nightmare, and the thing which not only promises wealth and success, but allows it to be achievable. Advertising, branding, slick PR all tie into this myth of inevitability. Corporations and the governments which enable them, talk of progress and prosperity. The white man’s burden has transformed into the white man’s commercial burden, a moral project which seduces the mind.

As John M. MacKenzie in his 1984 book Propaganda and Empire mentioned, the concept of ‘ideological clusters’, that is, of values and attitudes, synthesised a new type of British patriotism comprised of devotion to royalty, worship of successful national figures, militarism and imperialism as a sense of worth and power. Technology simultaneously helped the circulation of ideals and narratives. One was no longer limited to learning through direct experience, nor through their memories. Rather, people’s memories became prosthetic, circumscribed by a particular group with authority and power, in order to reinforce a collective consciousness which is passive and obedient.

Our cultural memory mirrors the power relations contained in the prevailing discursive language which is propped up by a system of dissemination, repeated in society to eliminate competing narratives and to promote the idea that corporatocracy can solve our economic and political problems. The Travel Association’s overseas propaganda, sponsored by private businessmen, worked well to rectify deficiencies in commercial propaganda during the 1920s, but gone are the days of overt ideologies. In the tradition of Foucault, ideologies became naturalised by those wielding the power and knowledge – welcome to the empty rhetoric which espouses the benefits of a false sense of individualism, deregulation, commercialism, consumerism and banking!

Just as British colonialism in India paved the way for future revolutions, so too has the financial and corporate world. People have had enough of artificial constructs without remorse and without reprimand, and are starting to take control of how we organise ourselves as human beings, and how we can live and experience the world around us.

Awesome article!